- Momentum

- Posts

- Developing Success

Developing Success

How psychological characteristics evolve to predict success

Reading Time: 5 Minutes

What to Expect:

Insight into what psychological characteristics matter when

Practical tips for developing your mindset

Why being self-referenced matters

Excellence is idiosyncratic. Everyone does it in their own way.

It's hard to figure out what separates the best from the rest.

There's no perfect psychological constellation of traits that guarantees success. Rising to the top of any high-performance endeavor, whether it be sports, business, medicine, or the military requires some things the science suggests are necessary, but not sufficient (e.g., IQ).

Because there are so many ways to reach the top - elite skill, mental makeup, some combination of the two, luck, hard work, and more - it's hard to pin down an exact profile of what it takes.

The best we can do is keep trying to figure it out and to surface themes that emerge across studies, types of athletes, age groups, and levels.

There's some good news here.

We do know that some things are more important than others, as they consistently surface in research trying to answer the question of who makes it and who doesn't, like:

Intelligence

Self-regulated learning

Conscientiousness

Commitment

Achievement motives

So, what mental traits should we be looking for to help figure out who is likely to make it and who doesn't have what it takes? And, what mental traits should we try to develop and instill in others to promote their success?

Psychological skills evolve in stages

As the research moves further along, we're beginning to see evidence of the old business idiom, "What got you here won't get you there".

Different psychological characteristics are required at different developmental touch points.

There is both good and bad news in that. The good news is that you can manage to make it out of one stage without fully mastering some of the psychological characteristics - talent will help you some. The bad news is, if you do manage to do that, it's only a matter of time before progressing through stages without the competence to match catches up with you.

Of course, you can't be equally balanced in all psychological traits. Recognizing that a different set of traits is required at each stage can help you identify skills to work on and potentially your own strengths and limitations. Going from the minors to the majors asks different things of you.

Past Links to Success

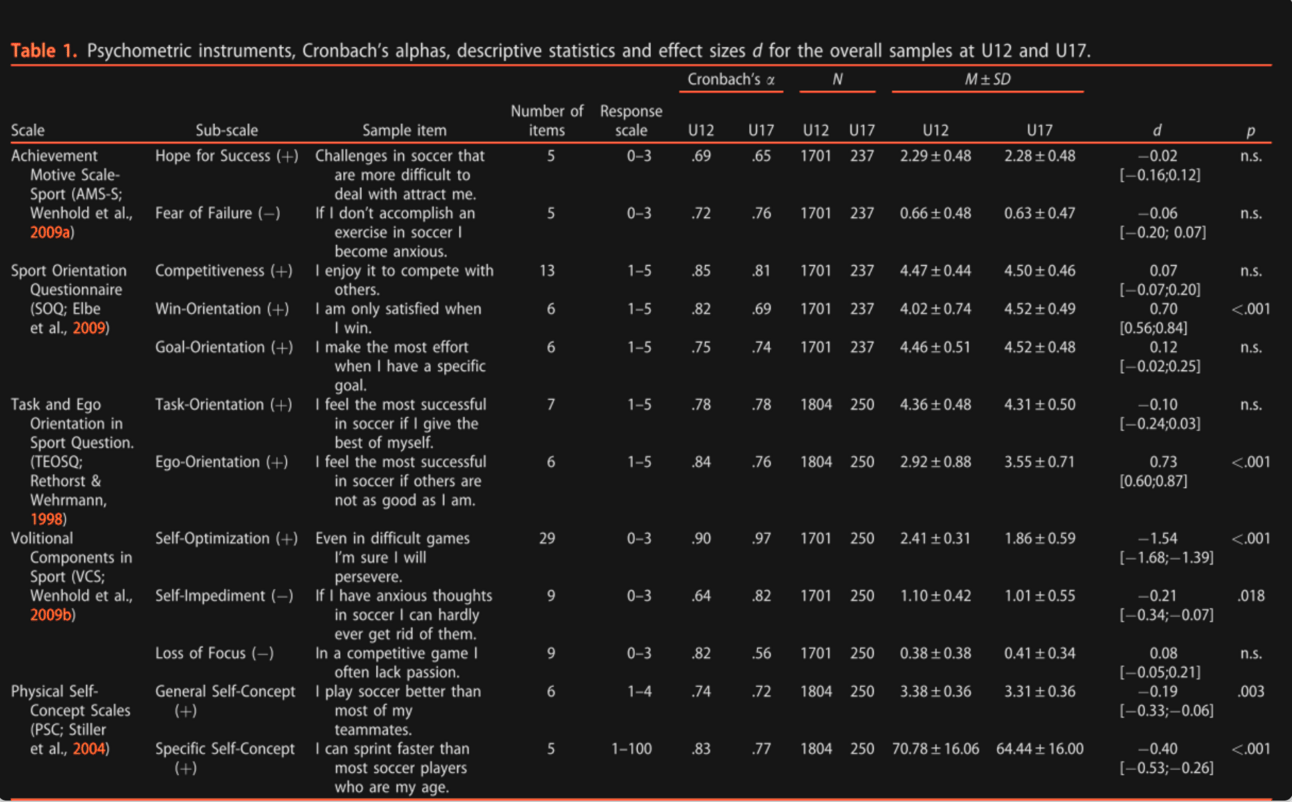

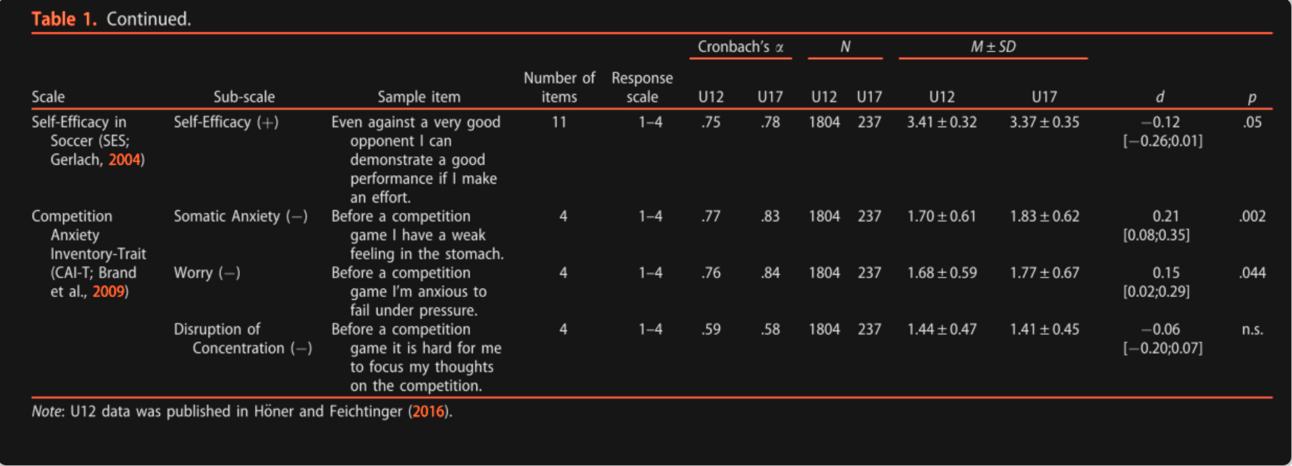

Here are some psychological characteristics that have been linked to advanced and success performance in past research:

Most of these attributes boil down to how people see themselves, the amount of anxiety they have, and what motivates them.

The study this is taken from is based on data from athletes under 12 who have entered an elite academy system and are now on the path to pursuing a life as a pro.

The more motivated they are to develop, compete, reach their goals, and win, the more likely they are to be successful. The more motivated you are to optimize yourself, the harder you'll work and the farther you'll go. The more you like and believe in yourself, generally and in your performance, the more confident you feel and the better you perform.

Though that all may seem obvious and straightforward, interesting patterns emerge as you start to see what characteristics lead people to stick around and what filters people out.

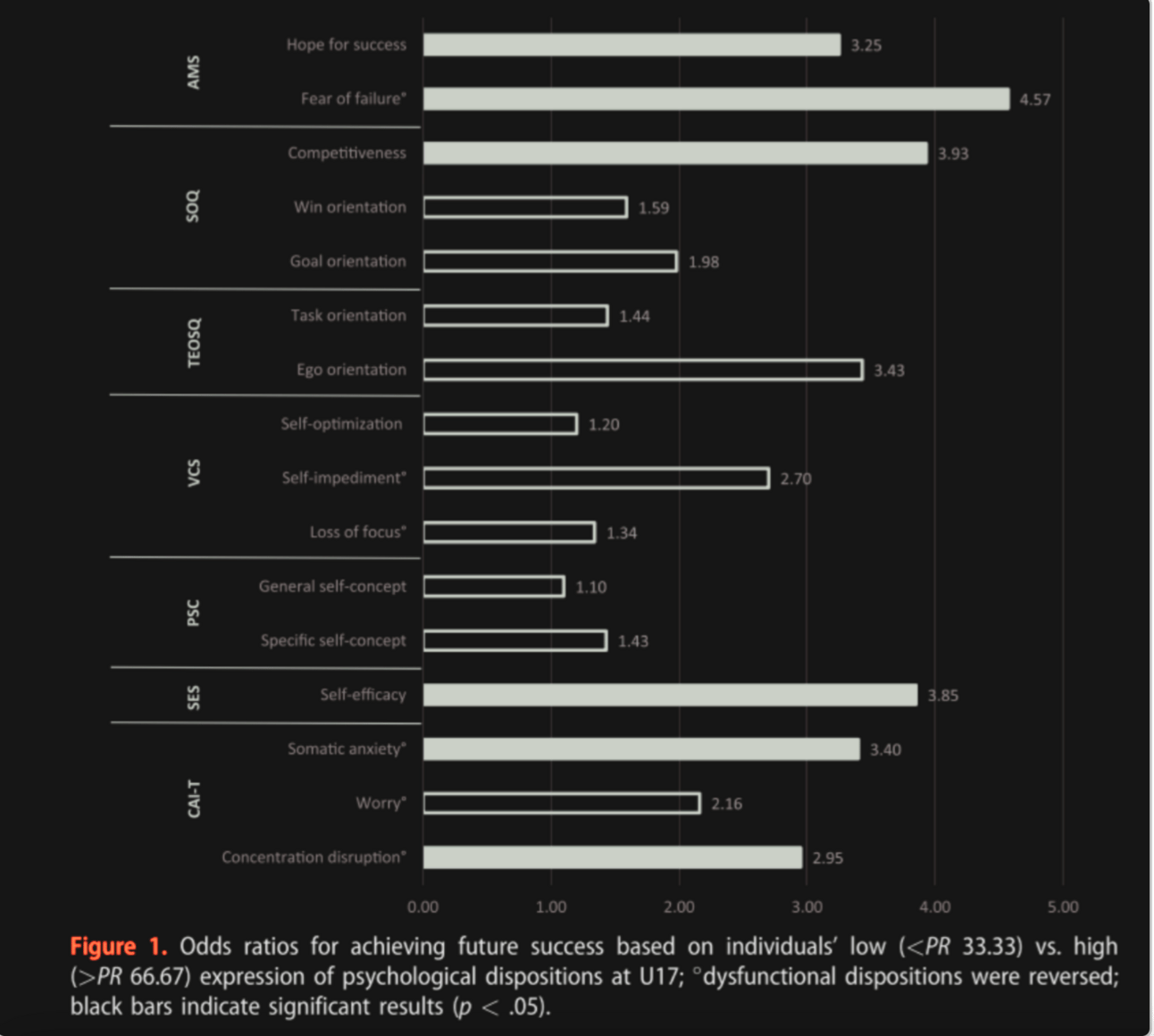

For example, you'll notice in the table above that both ego orientation (fixed mindset) and task orientation (growth mindset) are related to subsequent success. Being driven to win and having a stronger fixed mindset were more predictive of who stuck around in sports than being driven to learn or a growth mindset. Yet, as these same athletes aged, they started to experience the deleterious effects of these attitudes, such that anxiety increased and their drive to self-optimize decreased.

At the early stages, it seems it's most important to believe that you're better than others. At later stages, it's most important to focus on being better than your past self.

Developmentally, this thinking makes sense. When we're younger, it's easier to evaluate our progress by seeing how we stack up. But as we enter more competitive teenage years and beyond, social pressures start to impede the utility of focusing on other people more than ourselves. Social comparison becomes the thief of joy and creator of worry.

As athletes enter the later stages of their careers, the more negative sentiment an athlete has about themselves, the less likely they are to succeed. What pushes them forward is focusing on reaching their goals, personal optimization, and winning.

What this means for managing talent

As people progress, the reference group they are a part of becomes more and more elite.

The more elite it becomes, the more important it is for leadership to focus a performer's attention on their own individual development and progress, rather than how they compare to the rest of the group.

The more that a performer focuses on winning and becoming the best version of themselves, the better they perform and the more likely they are to be successful in the future. If they get caught in comparison with the other talented people they are surrounded by, the more likely they are to fall by the wayside.

We need to instill this mentality about being the best version of yourself as young as possible. If we can teach people to compete with themselves as much (or more) than they compete with others, there's a better chance that they can internalize an approach that leads to long-term personal development and success. Yet, our society places a disproportionate emphasis on how we stack up compared to other people. Even from birth, we're put into percentiles.

While these comparisons can be helpful from the perspective of evaluating norms, they also inevitably create a sense of worthiness when you don't quite fit what's expected. The same is true for any performer. If they haven't yet figured out what makes them special and are constantly compared, they're more likely to experience anxiety than motivation. The goal becomes to just be seen as "good enough," rather than to get better.

This research also points us in the direction of a few interventions that can be helpful for your high performers.

Beyond teaching your performers to be self-referenced in their progress, it can be helpful to raise their self-awareness and improve their process of reflection. Getting them to answer questions about their own development, confidence, and strengths would all be useful in this regard.

Finally, as your performers rise through the ranks and the pressure increases to win and compete, this research points to the necessity of a robust mental toolkit for sustained success.

This mental toolkit should help instill hope, focus on the process, and teach performers how to orient to controllables, rather than their own worries.

We explain the latest business, finance, and tech news with visuals and data. 📊

All in one free newsletter that takes < 5 minutes to read. 🗞

Save time and become more informed today.👇

References

Wachsmuth, S., Feichtinger, P., Bartley, J., & Höner, O. (2023). Psychological characteristics and future success: A prospective study examining youth soccer players at different stages within the German talent development pathway. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 1-25.

Reply